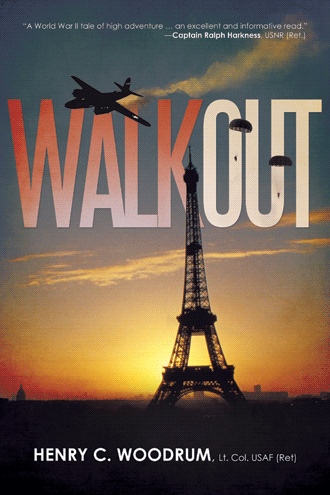

A book by Henry C. Woodrum, Lt. Col. USAF (Ret)

Description

Ten days before the D-day landings at Normandy, Lt. Henry Woodrum woke early to fly a combat mission that culminated in being shot down over the northern suburbs of Paris. Expected to be captured as he hung suspended in his parachute over Nazi-occupied France, Lt. Woodrum never lost hope—even as he realized the Germans were trying to kill him before he hit the ground.

Lt. Woodrum’s thirty-fifth combat mission flying the Martin Marauder B-26 was supposed to last just a few hours, but it ended up continuing three months as he struggled to survive in war-torn France. In his fascinating war memoir, Woodrum shares his true account of how he managed to evade capture while being aided by the French Underground—some of whom paid the ultimate price for their loyalty to the downed American pilot.

Walkout not only relays the incredible story of a young American behind enemy lines during pivotal months of World War II but also illustrates the quiet heroism displayed by American airmen and the French Resistance during an unforgettable time in history.

“A true story of a B-26 pilot’s escape from the Nazis after bailing out over Paris. A must read!” —Col. William F. Nicol, USAFR, MC (Ret)

Here’s an excerpt:

I stood where Morgan had been just moments before, leaned down, pushed out, grabbed my knees, and left old Y-5-T forever. The sudden change was startling. I was surrounded by silence and lulled for a moment into an almost dreamlike unreality. It seemed as if I could stay that way forever, just floating along. It was a deeply satisfying feeling.

I began counting, but then realized I’d already fallen quite a distance. I counted anyway, up to six or seven, before pulling the ripcord. I caught a glimpse of the ground, growing much closer now.

Nothing happened.

I pulled the ripcord again, the metal ring feeling cold and hard in my hand as I flung my arm outward, tugging. Then came the shock of the chute opening, not as violent as I’d expected. It was my first jump. Above me, I could see the whiteness of the silk canopy billowing in the air, fluttering with little noises as it formed into bulging roundness.

I felt an overpowering sense of exaltation at just being alive, knowing that I would drift to the ground and go on living a little longer. With that thought, I realized for the first time how strong my fear of getting hit and blowing up had been. Instinctively, I looked at my wristwatch. It was 11:43 a.m.

I thought about the others and turned my head from side to side looking for chutes. I couldn’t see any and wondered where they were. I twisted and turned my head and finally saw two chutes much higher to the east, then a third, beyond and above the other two. I counted again. There were only three; there should have been five. Where were the others?

I focused on the ground and spotted the Eiffel Tower and the Arche de Triumphe a mile or so to the south. The Seine curved and twisted its way through the city. Suddenly I remembered our briefing officer’s advice—avoid Paris at all costs—and laughed aloud. I looked around, craning my neck from side to side to find the plane, and finally saw it off to the north, below me. Smoke spewed from the fuselage, which was burning fiercely now, wild flames engulfing it.

As I watched, it augured into a vacant area surrounded by buildings on three sides. It was the only open spot where it could have hit without demolishing something. I guessed that I’d land on the northwest side of the city, most likely among some buildings. To the west, I saw a few open fields. I doubted I’d drift that far. The streets were empty. There were no people around; they were probably in air raid shelters.

Just ahead and below me, a burst of flak exploded with a loud WHUMP. It was so near I saw the burning crimson of its center as white-hot shrapnel screeched past me. Out in the open like this, the explosion was deafening, and my feeling of exaltation fizzled as I realized they were trying to kill me before I hit the ground.

One man, alone, dangling helplessly in a parachute. “You dirty, God-damn sons-of-bitches,” I shouted.

Another burst dotted the sky on my right and I shouted again, outraged that I might have survived all that flak on the bomb run, just to wind up a corpse in a parachute. Then another round appeared and I cursed them at the top of my lungs. The war was suddenly too damned personal, and I was furious.

Now, I was drifting faster. The arch was already some distance away and the open spaces I’d seen were closer. The ground was coming up fast. I began to relax again as the firing stopped, thinking I might have a chance to land in an open field. Out of habit, I reached for a cigarette, but I’d left my jacket in the plane along with my Luckies.

I stretched against the harness and checked the terrain below, wondering how long I’d stay free after hitting the ground. I saw a few people below now. I then floated over a field and past a populated area with more people in the streets.

Small arms tracers whizzed toward me, but fell away just short of their mark. More tracers curved upward from the ground, red fingers reaching out greedily, and I wondered if I’d had it.

The ground was rushing toward me now, and I could easily distinguish people below, all of them hurrying along, some glancing up at me before running toward the spot where they apparently thought I’d land.

Tracers still whined past, closer than before, and I began pulling on the shroud lines in a side-to-side motion. Finally, I decided it wasn’t doing any good, especially after I pulled too hard and spilled air from the chute, which caused me to very quickly drop for a few feet before the chute again filled with air.

When I stopped swinging, the firing also stopped. Did the gunners think I was dead?